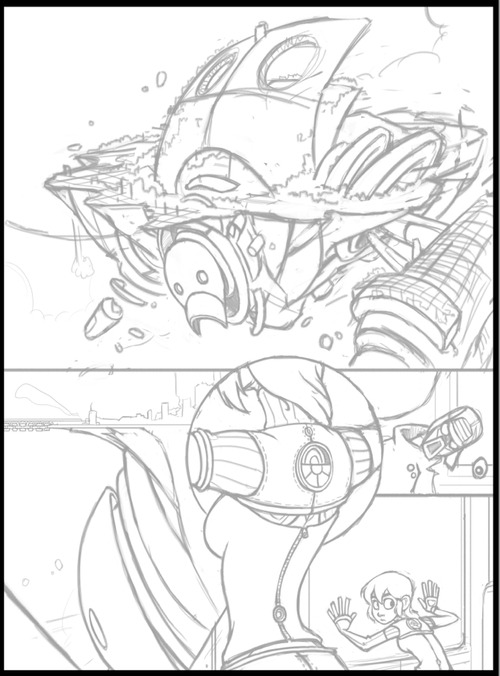

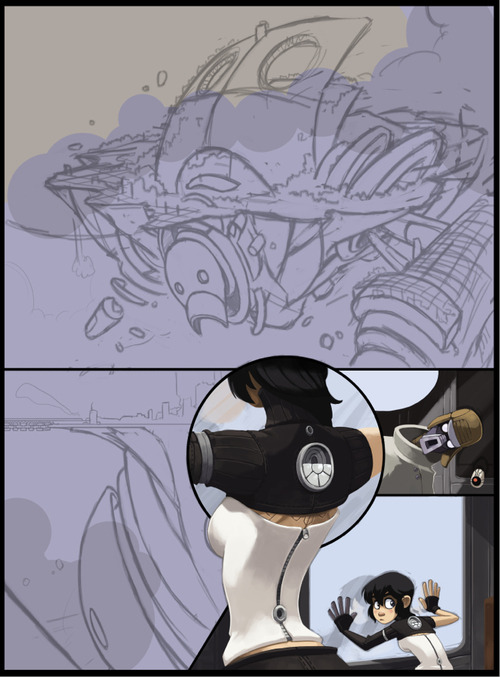

It starts with a rough outline. For Dark Science I have a basic script and story outline, and I decided how much of that script can/should fit onto a standard page. From there I start working out what I needed to draw.

Concept Sketching

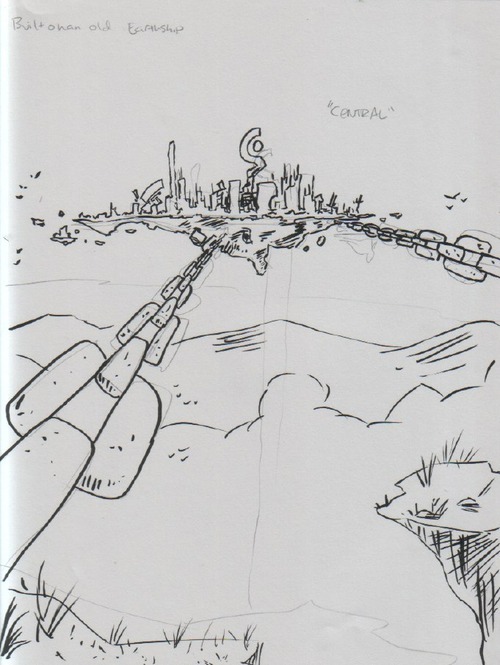

With this page I started with sketching Nephilopolis. Having written the story ahead of time, I already had a rough idea of what I wanted, but not the details. I started by going back to my first sketch of the island I did months ago (before I’d finished the plot).

A very rough idea at this point. Once I got to this page in the story and actually solidified the notes about the setting, I began fleshing it out:

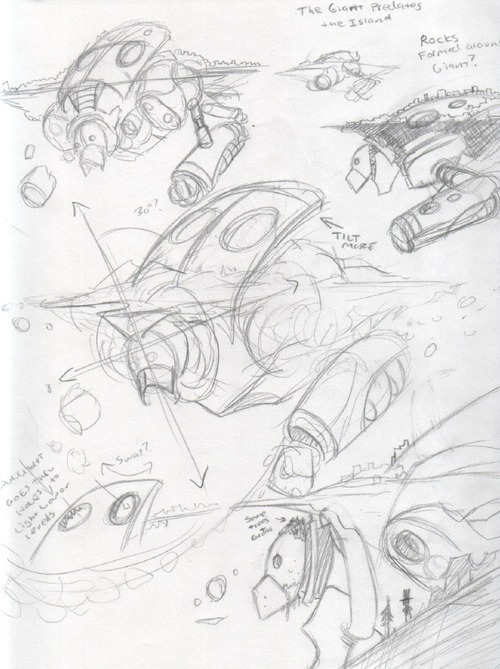

Here I’m just sketching out possible elements. I wanted to make the head clearly recognizable, and also for the giant’s shapes to contrast clearly with the shapes of the island. At this stage the design was still fairly symmetrical. After I was comfortable with the basic idea, I set the giant at an angle to the island and worked on more details:

Although at this point the design wasn’t “finished,” but it was enough to get started on thumbnailing the comic:

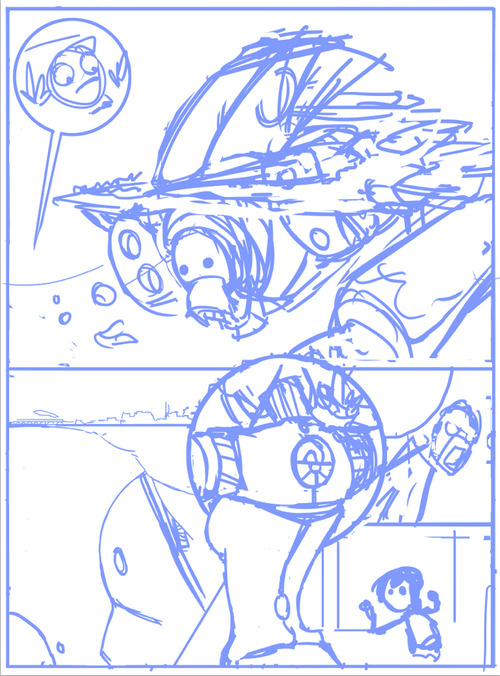

Thumbnail

Using a standard hard round brush in Photoshop, I quickly and roughly start working on the basic layout of the page. From the “script” I have directions as to what needs to happen in the scene, but I don’t worry about the specifics of the dialog until later, as it will depend on how the images end up shaping.

Pencils

Using a textured brush that looks a bit like pencil (there’s no need for this, just a personal preference), I start “pencilling” the page, solidifying the forms and rendering all the details that I don’t want to forget about when I start to color. With the Nephilopolis island I left things rougher, as I know from experience with landscapes that I end up improvising a lot when I start painting. By contrast, Kimiko and the stranger are tightly rendered, as they’ve already been fully designed and introduced in previous pages.

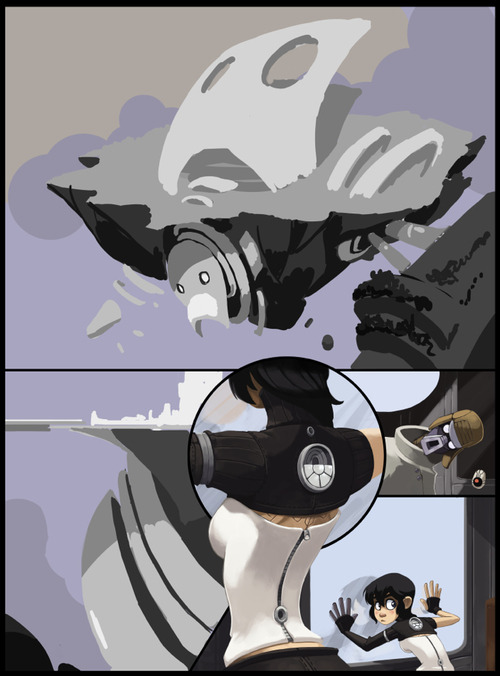

Painting

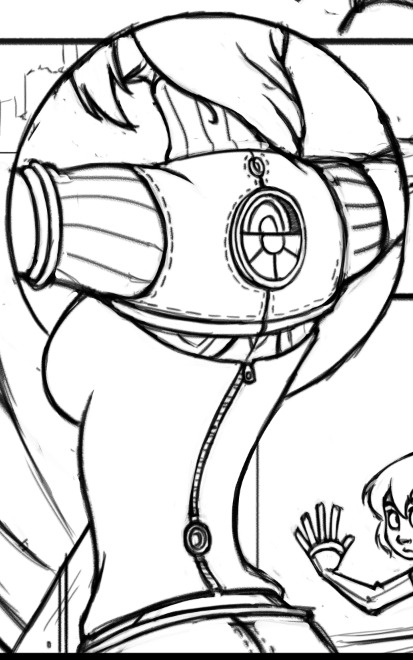

I’ll use a specific section to illustrate the steps I normally take with painting.

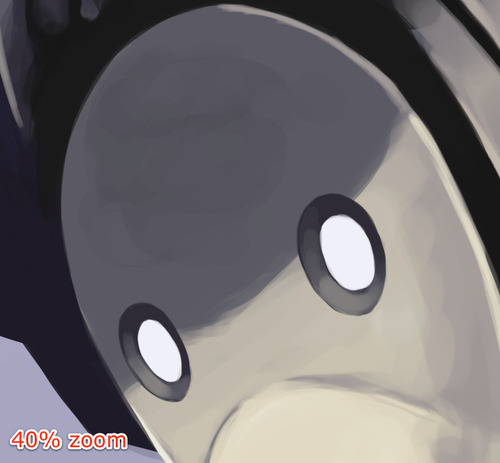

Step 1: Colored Lines

Using a round hard brush with pressure sensitivity controlling both opacity and size, I draw out the basic outlines. Even though often these outlines won’t be visible, it’s a good starting point for blocking in colors for the next step and ensuring the edges of the figure are smooth. I only generally use this step for figures, as I tend to give them sharper edges so they’ll pop out a bit.

Step 2: Blocking in Colors

Underneath the lines layer I start filling in the basic colors. I’m not concerned with detailed shadows and lighting just yet, only making sure the general colors are where they need to be. At this point I’m working with four layers: one set of lines & colors that go underneath the black borders (the top half) and one set that go on top of the borders (bottom half).

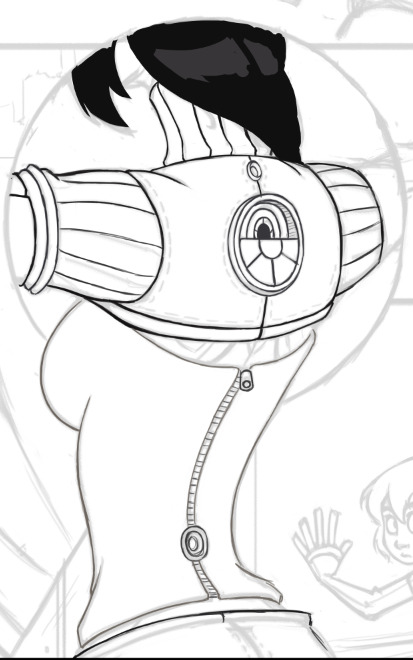

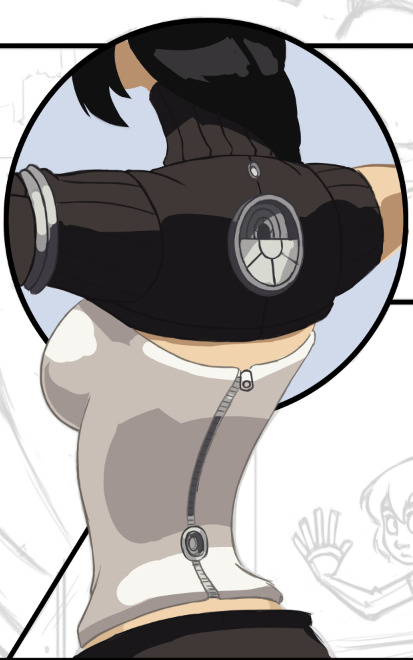

Step 3: Flatten and Render

From here I flatten the color layers with their respective line layers and, with a round brush set to opacity sensitivity (no size sensitivity), I begin painting. As you can see, some of the lines I’ve left and some I’ve removed; it all depends on what’s needed. Also note that this actually looks slightly different from the “finished” torso in the comic, as I went back a couple times and tweaked some details. No piece of the comic is totally finished until everything is finished.

Rendering the Island

With this page I started with the “known” elements (Kimiko, the stranger and the train car all had set designs and shapes) and worked my way to the “unknown” (the island). I dropped in a basic filler for the sky and started to think about the tonal values.

Setting up Tones

For a very complex image that you haven’t painted before, it’s easy to jump into it with lots of colors, guns blazing, but you run the risk of losing appropriate contrast and overworking key areas. For these situations I prefer to make a grayscale “underpainting,” where I work out the appropriate tones. I don’t allow myself to blend anything or use colors at this point. Once I’m satisfied with the basic lighting, I move on to color selection.

Here I’ve begun testing colors. I decided at this point to remove some of the border lines. I found them to be distracting as I started to have a better view of the composition. I’ve also moved the robot portions to their own layer and hidden it for the time being, letting me focus on color selection and rendering of the rock and island portions.

Rendering the robot portions begins, leaving the details of the top portion sparse for now, as it will be mostly covered by the city portion.

Toying around with the colors of the cityscape. Not concerned with details yet.

Most of the city is rendered at this point. I’m leaving the robot’s arm until later, as I’m not satisfied with how it’s playing against the rest of the picture.

Nearing completion. Fleshed out the clouds and added some contrast. Still toying with the arm.

Finished up the arm, and added the final text bubbles. Done!

Author: Alex Heberling

Untitled

I’m more excited about my new inspiration blog than about actually making art today. .__.

Ehhhhh, I’ll get over it. ^_^;

Untitled

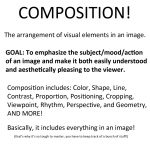

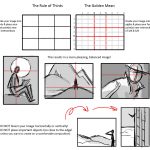

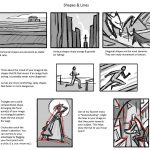

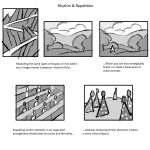

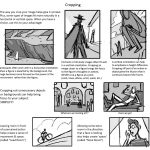

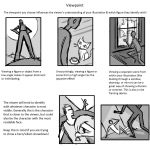

Today I gave my students a quick presentation on some of the basic considerations for composition, which I am now sharing with you! I’ve given them separate talks about color and tonal value/contrast, which are also super important compositional concerns. (I’ll be sharing those presentations too once I properly format them)

I personally love learning about different compositional techniques. It’s fun to think about the ways that the brain views & sorts images, and how we can trick it into feeling a certain way or looking at certain aspects of an image first! It’s easy to fall into compositional ruts (which I am also guilty of) because a lot of art gets by with mediocre, though serviceable, compositions. If you can generally understand what’s happening in an image then it’s generally fine. However, it’s the truly great compositions, where everything in the whole image has been considered and ‘clicks’ together, that bump up an illustration to a visual slam dunk. NC Wyeth is one of my favorite artists for this reason: his compositions are rock solid, varied based on the image’s intent, and always enhance the mood or action he is depicting.

For extra reading, some online compositional resources that I’ve found helpful or interesting include:

Creative Illustration by Andrew Loomis (download it for FREE. Such a great book all-around.)

Gurney Journey (check out the “Composition” tag, but really everything he posts is great)

The Schweitzer guide to spotting tangents

Cinemosaic (a blog by Lou Romano with some truly WONDERFUL compositions captured from various films)

Where to Put the Cow by Anita GriffinHappy composition-ing!

A solid breakdown of the fundamentals of composition, complete with examples!

Untitled

(tutorial)

i just did a cool thing that i think would be useful if you’re like me and sometimes have a hard time picking colours / a colour scheme for an image

basically i just took a brush with moderate spacing, turned on colour dynamics and set all the hue/sat/brightness to a low (~10%-30%) jitter, picked a base colour, and drew a line down the side of the canvas

it’s sort of like when some people save colour swatches so they can keep their shading consistent, but more for playing around with different tones and lighting on a single surface. it’ll probably be pretty good for skin which is very multi-tonal by nature.

a lot of colours came out that i probably wouldn’t have picked manually, but they still looked pretty cool. and it saves a lot of time because now i have a broad range of colours without having to browse through my pantone swatches or open up the colour picker.

Twelve Things You Were Not Taught About Creative Thinking In School

Twelve Things You Were Not Taught About Creative Thinking In School

Some inspiration to get y’all pumped up for the week!

An excellent breakdown. The most important, in my opinion, is “creativity is WORK.”

5 Essential Superhero Redesigns!

Seeing as how I’ve done both the top ten for best and worst superhero costume redesigns, I feel obligated to put my money where my artistic mouth is and take a stab at fixing or updating some of these costumes. I’ll be taking a similar approach to my earlier take on Batman & Robin, where both the back story and design of each character are fair game. I’ve done five here, and chose them based on one of two criteria:

- It’s a particularly awful outfit that doesn’t fit the character, or

- It’s a solid character who just needs some updating or tweaking

I’ll list these in order of “reboot depth:”

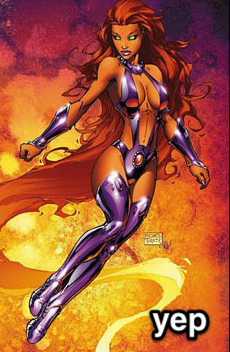

5. Starfire

What’s wrong: In the wake of DC’s “new 52” this felt like a no-brainer. Starfire is a decent character who’s always, in my opinion, gotten the short end of the costume stick. I get that she’s supposed to be sexually liberated and somewhat polyamorous, and that’s fine, but dressing like a John Carter’s Princess of Mars-themed stripper doesn’t cut it. Really, up until the Teen Titans cartoon she’s always been in the most awkward and impractical getups for someone fighting crime.

The Fix: I went for the simple route and took some notes from the cartoon (notably the skirt). I wanted to make sure it kept the bubbly, innocent feeling of the character while also hinting at some power (with the exposed arms here). The overall effect is meant to convey someone who’s tough, cheerful and comfortable flying around in the air.

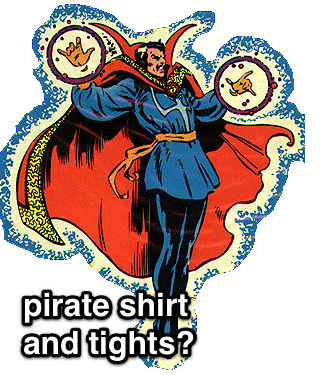

4. Dr. Strange

What’s wrong: I love Dr. Strange, but he’s always had the worst outfits. For a guy who basically hangs out in his house in the West Village, he seems to always wear the most ostentatious getups. He’s not an alien from another planet or from some culture that would dress that way, he’s a grown man who became a wizard well into adulthood. Nothing wrong with having some style while you’re maintaining the balance of the mystic planes.

The Fix: Two parts Vincent Price, one part Christopher Lee and one part Dr. Orpheus, this Dr. Strange is still magical, but with a more coherent design direction.

3. Ms. Marvel

What’s Wrong: Simply put, I think it’s embarrassing for Marvel to showcase a prominent character like Ms. Marvel and have her wearing that outfit. It’s just so tacky, and tells us nothing about the character. Basically they just changed the colors of Jean Grey’s Phoenix costume and exposed more skin. Come on, guys.

The Fix: Since her origins are ostensibly tied with Captain Marvel, I decided to go a route that’s more along the lines of the Ultimate Marvel version of that character, where her abilities come from alien technology rather than vague space magic. The notion that she’s, for example, permanently bound with this technology that she doesn’t fully understand can make for some interesting stories. There can be some potential with this character again with just a little bit of tweaking.

2. Wonder Woman

What’s Wrong: Wonder Woman, in my opinion, is a character that’s always been on the cusp of being really neat but never quite making it like Superman or Batman. Although a feminist pop icon, her origins are too tied up with creator WIlliam Marston’s obsession with bondage. Because of this (and an all-too-frequent parade of poor or sexist writing), she’s never had a solid, progressive design. The 21st century can update this character.

The Fix: One part Thor, three parts Xena. I’d push the mythological angle further. Just as nobody thinks of Thor as “Superman with a hammer” I don’t want Wonder Woman to be “girl Superman,” as she’s sometimes seen. I’ve also tweaked her origin slightly, making her a more literal “statue come to life.” This isn’t as extreme as it seems: in regular canon, Wonder Woman’s origin was that she was formed out of clay by the queen of the Amazons, and imbued with the powers of the Greek Gods. (Note: I am well aware that Greek statues were painted, but for aesthetic & thematic reasons it doesn’t work here. She’s just an old statue, so there wouldn’t be paint.) This, I think offers more story possibilities if she’s less literally human, physically. Her personality would remain the same (nothing more fun than the perspective of an Amazon in the modern world), but we now have an added Greek layer of Pygmalion or Telos.

The costume change is mostly conservative. Because of the strong fetish associations (and overall impracticality for a fighting Amazon), I’ve removed the lasso in favor of more traditional Greek weapons. The overall effect is intended to push Wonder Woman’s core themes further while making her also stand out as more than just “the female superhero.”

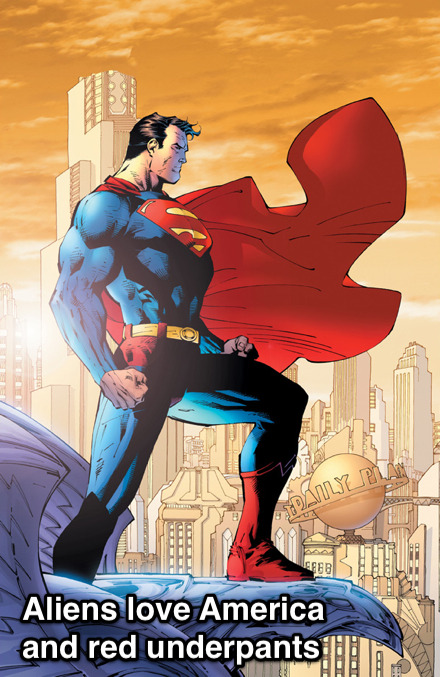

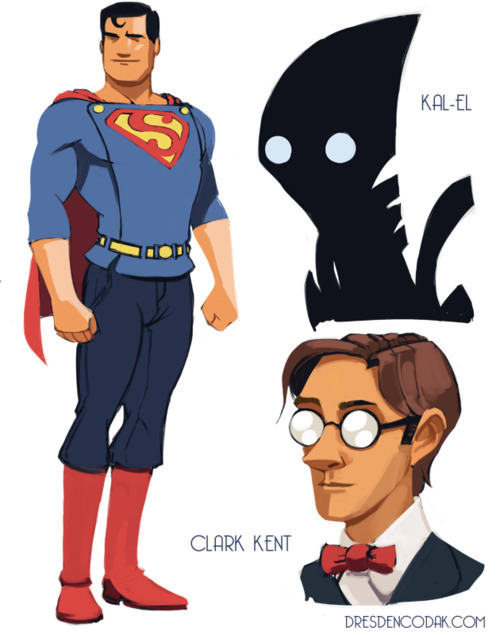

1. Superman

What’s Wrong: Since his creation, Superman’s drifted from being a progressive champion for the common man to a patriotic middle-America boyscout who represents the establishment and traditional values. When he was developed in the 30s, Superman was very much a Depression-era hero, mostly going after villains like crooked money lenders and saving people who were being abused by the system. His superpowers came from the fact that he was from a more advanced society, and his morals too were because he was simply a brainier, more sophisticated guy. During and following WW2 and into the Cold War, though, he became an official symbol for American values in particular (it was originally “Truth and Justice,” without “the American Way”). He was now not just an alien, but an alien raised by simple Kansas farmers and his abilities had a more generic “superpower” explanation. This is all fine, really, but I think the original concept is more compelling these days.

The Fix: Two parts Martian Manhunter and Ten parts Fleischer Superman. “Superman: the Man of Tomorrow, Strange Visitor from Another World.” I really want to push that. First off, Kryptonians should actually look like aliens and not white people. Here I have Kal-El from a race of beings whose technology and biology are long since indistinguishable (Clarke-esque space gods, you know the type). They’re strange to our mortal eyes but mean well. I’d keep the “destroyed planet” origin but more heavily emphasize the “non-interference” part of Superman’s mission statement.

If you’ll remember from the 70s movie, his father Jor-El told him he was forbidden to interfere with the course of human history, but when you think about it, that’s kind of vague. What I’ve done is added a Star Trek or Uatu the Watcher kind of prime directive to all advanced species: Kal-El can’t let people know that he’s an alien, nor can he openly interact with them using advanced technology. Still, he’s a compassionate guy and wants to help, so he takes the form of “Superman” to inspire the mortals in a constructive way. Also, the notion that he can take on different forms means that the Clark Kent secret identity need not be as bad as it currently is.

The costume redesign holds to the basic themes but makes it a little more working class. The buttons at the top are meant to invoke overalls, and the sleeves are cut a little higher for someone working with their hands. I’ve removed the spandex and gone with looser fitting slacks, while keeping a short cape and boots, since he’s still an adventurer.

Overall I want to evoke a classic Superman feel while making it a little more modern in its exploration of the sci fi themes. He’s still basically the same guy: an alien from another world looking to fight injustice, but without the overt patriotism and a quirkier execution of the secret identity.

*********************

So there you have it. I’ve hope you’ve enjoyed my superhero costume trilogy!

A gentle reminder: If you changed your Facebook profile picture, you should go do something real, too.

I’m not knocking the red — in fact, red Grumpy Cat is currently what Facebook thinks I look like — and I’ve heard from many LGBT friends, particularly older ones, that it’s a touching reminder of all their straight allies.But it is not, in and of itself, work. And if you want to carry this mantle, if you think it’s important (and I hope you do) then put some skin in the game. Volunteer for a group that advocates for queer rights; donate a little money; figure out what your talent/ability is and offer it.

Figures: They Speak For Themselves (mildly NSFW)

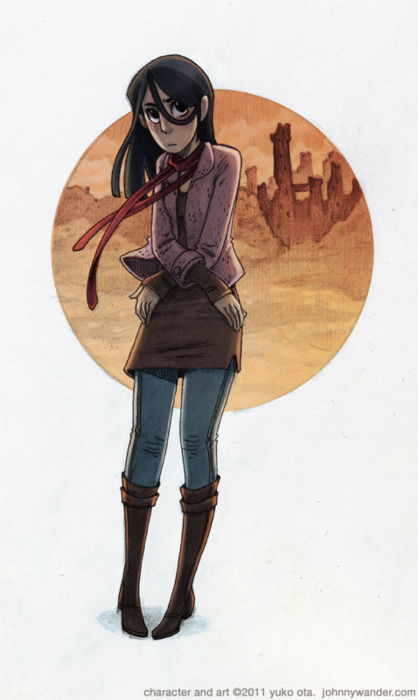

Continued from the last article about costume design, today we’re going to talk about those wacky things you hide underneath clothing. Figure drawing is a pivotal tool to any artist, but being able to effectively render humans and creatures is only part of the equation. Even if your draftsmanship is solid, you won’t get far if your designs are uninteresting. Effective and dynamic figures are the cornerstone of having compelling characters in pretty much any comic.

The Purpose of Character Design

The focus of art in general is to generate a particular response out of your audience; the mechanics of what you literally create are often secondary to this goal. Something can be abstract or literal, but the point in both cases is the effect is has on the viewer/listener/reader; the creation itself is a means to an end. In comics, authenticity and realism are not defined by what you are actually drawing, but rather how your drawings are viewed by your reader. In the context of a visual narrative, a simplistic drawing can be “more real” than a more realistically rendered one if that simplistic drawing evokes a more authentic response. A stickman can be a more convincing character than a photorealistic painting; it all depends on how that stickman is conveyed.

When you design your characters, you have an opportunity to both communicate information about them, as well as provide a conduit through which information about other characters and even environments can be shown. Their appearances can augment the actions in the narrative, or even take the place of regular action.

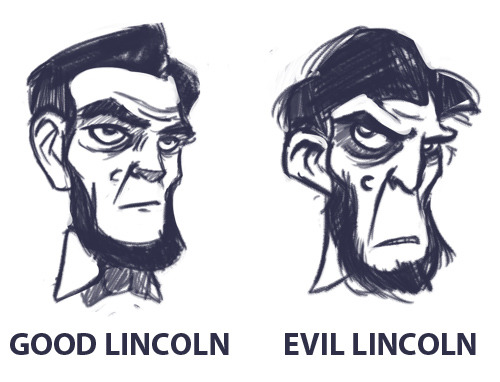

Focused Caricature

When designing characters for comics, then, it’s not universally important to faithfully recreate how people look in real life or even caricature real life. This may sound contentious at first glance. After all, isn’t a big part of cartooning exaggerating elements of real life? Certainly, but that’s only half of the equation when it comes to visual narratives. A regular caricature is mostly about emphasizing what’s visually obvious, and while that’s still present in comics and animation, on top of that there’s often the need to convey information about the character. Even if you’re basing a design on a real person, what you choose to emphasize can determine how the audience views that character. Again, what part of “reality” (in this case people’s appearances) you select to share can profoundly change how those characters are perceived.

Implied Motion

While they can be very similar, a fundamental difference between the needs of comic design versus animation design is the presence of literal motion.

In animation you can give your character a nervous tick, a particular walking pattern, or any other number of facial and other motion cues to add flavor and depth to a character. However, with the static images of comics, this approach is limited. As such, more pressure is placed upon the designs themselves because they’re the primary visual resource the reader has for gaining information about the character. Luckily, there’s a plethora of tools at our disposal for doing just that. The shape, size and position of a figure can be designed in such a way that it implies motion. Upturned brows and lips can suggest someone who is frequently bemused, an exaggerated posture can give the impression of a certain type of gait, and so on. And since the reader’s eye can dwell on a comic panel indefinitely (at least in theory), there’s more freedom to employ subtler facial and body elements to add to a character’s flavor.

The Body

Shape Up

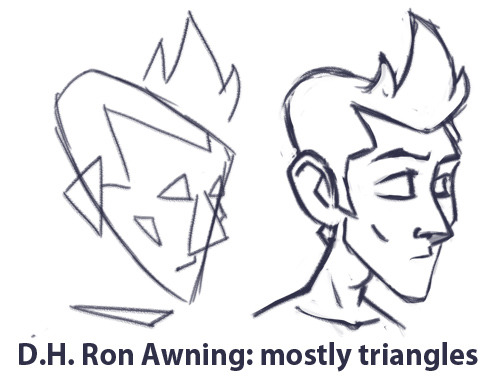

Silhouettes and overall shape are the first pieces of information to reach the reader, and because of this they will always dominate any character’s design. If your silhouette isn’t doing its job, the rest won’t matter. Starting with a simple, clear shape and working backwards is a good rule of thumb. And while this is naturally easier with monsters and other fantastical creatures, it applies just as much to regular people.

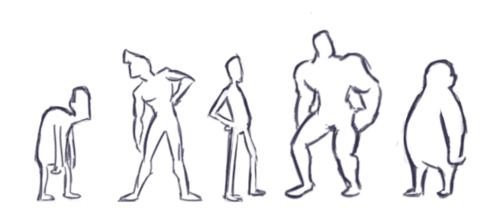

Body Types

People are not divided into skinny/fat/muscular. While these body states do obviously exist, each of these will still differ from person to person. For example, there’s not a single “athletic” body type, but dozens (as this amazing photo series shows). Don’t fall into the trap of old superhero comics where everyone looks like a bunch of clones wearing different costumes. People’s builds, postures, hands, feet and musculatures are extremely diverse, going far beyond simple factors like age, height and weight.

Body Language

Your character’s motions can inform you quite a bit on how you could design their form. If a character often stoops or shuffles, you can warp his or her spine and posture to bring attention to that sort of behavior. In general, you want the figure to emphasize and accentuate the type of body language indicative of that person. This is really important. In animation, there’s a little less of a required connection between body language and design because you can literally show motion, but with comics being a static medium, you have to imply a lot of motion without showing it. Naturally, if your character has a very wide range of motion, your design should reflect that too. Main characters aren’t usually designed around a single posture, for example, but side ones often are. In the end, this is all a tool to efficiently communicate information about a character to the audience.

The Head

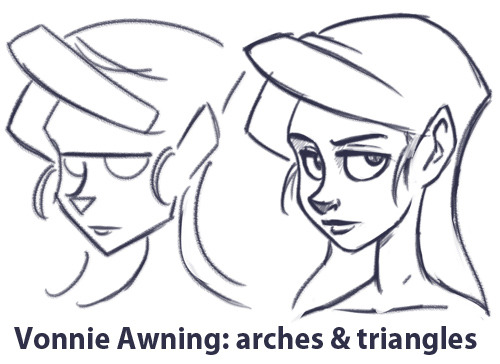

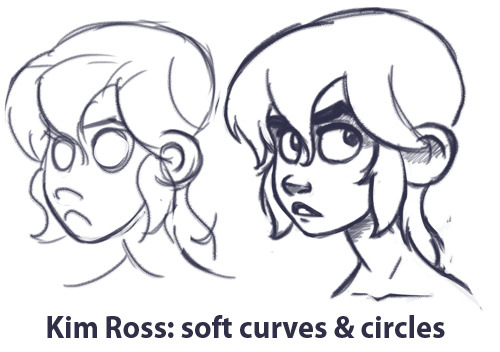

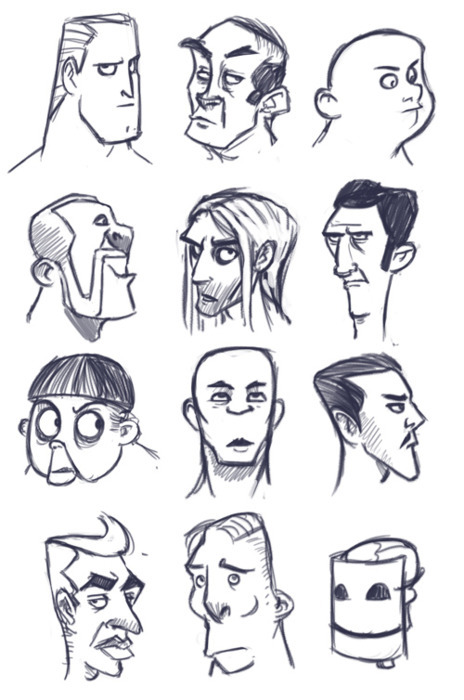

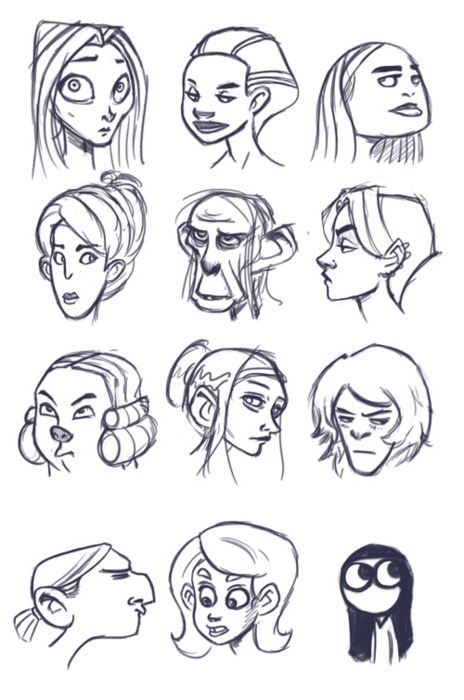

Shapes Again

Even more so than with the body, you should be able to reduce each character’s head to a fairly recognizable shape. This is the foundation for developing a good head silhouette, which is vital because the focus of a page is often on peoples’ faces; recognition should be established on a subconscious level with little to no effort on the part of the reader.

If the reader can’t immediately and clearly distinguish who is who without using details, the designs are bad. Also note: using hair alone to distinguish heads is cheating. Similar to the superhero body problem, don’t fall into the crappy anime trap of having identical heads that are only distinguishable by their wacky hair. Obviously hair is a component of character design, but to rely exclusively on it is taking a shortcut that only ends in sloppy composition and no variety.

Similar to the Naked Test (which we’ll talk more about shortly), you should be able to immediately distinguish all your character’s heads without any adornments or hair. Shave ‘em down and compare.

Variety is Your Friend

Ears, eyebrows, skulls, eyes, eyelids, noses, cheekbones, nostrils, hairlines, necks- these are all elements that will vary from person to person. Don’t be afraid to go beyond normal human proportions. Exaggerating or simplifying to the point of even being a stickman is perfectly fine, so long as it suits what you’re trying to do.

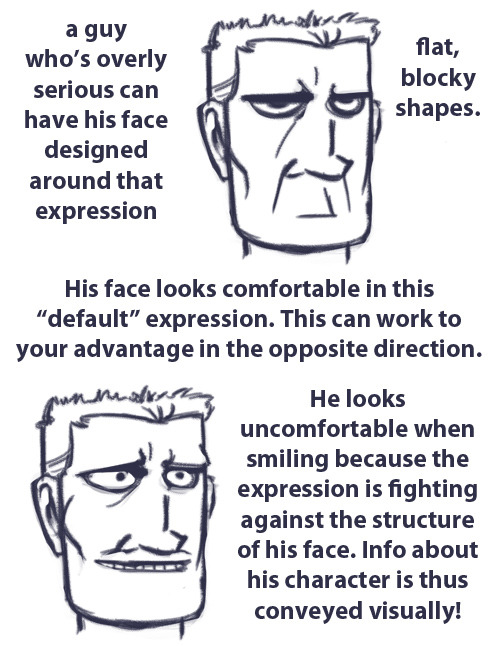

Dominant Expressions

What types of facial expressions and body language do your characters exhibit? Main characters generally require more of a range than side characters, while less three-dimensional characters can be designed to fit only a handful of expressions.

A lot of character information can be shown to the audience this way. Showing rather than telling your readers means you’re playing to the medium’s strengths.

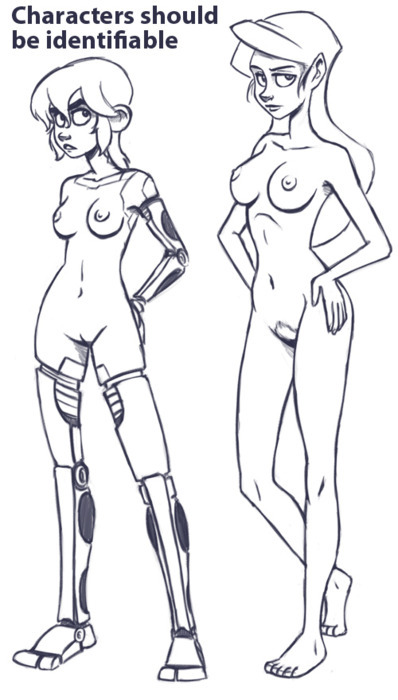

The Naked Test

Once you’ve designed your figures, we move on to the Naked Test. When developing a cast or even just a couple of characters, they should always be instantly recognizable without the aid of clothing. Even if their clothes have some key distinguishing elements to them (which they probably should), the bodies themselves are the foundation, and if the foundation is too generic, then you’re left with a flat design that can’t be corrected by adding stuff on top. All the basics should be present at this level: distinguishable silhouettes, unique body types and proportions, and unique facial shapes should all be there to tell your character’s story.

Figure drawing isn’t easy. Because we’re hard-wired to distinguish even the tiniest variance in human appearance, there’s a lot of pressure to get figures right compared to other subjects. As such, it’s easy to play it safe with conservative designs that don’t strain our draw-muscles, but it’s important to push past that. Effective and compelling character design is a skill that’s indispensable for cartooning of every kind.